November 2003 Issue

![]()

Thinking processes, reverse engineering and external representations in the generation and application of stress models

By Dr. Lorraine Cleeton, St. Bonaventure University, NY

Abstract

Introduction

Two major difficulties arose in a course on stress

management. Firstly, the students were dichotomized between those who, as

‘clients in stress’, had problems themselves and those who, as

‘counselors’, wanted to help other people. Secondly, the solutions to novel

problems presented by the ‘clients’ were not always amenable to solutions

suggested by the ‘counselors’. To

anticipate this polarization of the students the initial aim of the course had

been generalized to ‘Eliminating, minimizing and controlling stress in

ourselves and in other people’. Adding

to the difficulties, a literature review revealed many researchers maintaining

that stress has not been precisely defined (Everly and Rosenfeld 1981).

For the second run of the course, an additional aim was

added – ‘Gaining skills to transfer to transfer to new and novel outbreaks

of stress’. It was hoped that this

would facilitate students to counsel people outside those taking the course, but

they reported many failures. The aims were screened into a series of objectives

against which evaluation was made by assessed tasks following each two-hour

session.

Stress

Models

Information

overload (‘Tap and Jug’) model

Most

of the students brought along with them the naive model of stress caused by

information or emotional overload. This assumes that the organism has just so

much to give and that problems arise when that limit is exceeded.

Powell and Enright (1990) called this the 'Tap and Jug' model -

Tap and Jug

model

The

strength of this model lies in simplicity, but its weakness in the variety of

capacities of individuals for overload and the variability of their reactions to

stimuli (Eysenck 1989). For example, prisoners able to tolerate confinement and

torture may still have a fear of spiders in their cells.

In early assignments the students most frequently applied this model as a

default, sometimes used legitimately, but more often to fall back on in

desperation when other models had failed.

Yerkes-Dodson

Law

Capacity –

Demand model

Many

people feel stressed when the size of their workload approaches their perceived

capacity for work. Stress increases

as more work is added, eventually to exceed the perceived capacity.

Ideally one hopes that the workload will decrease, but sometimes as a

result of the stress we are scarred and our capacity is reduced.

If you come to terms with it or receive counseling, it is hoped that the

workload might once again just fill the capacity.

A better solution would be to achieve more stamina so that there is

increased capacity, i.e. the ability to withstand a greater workload in the

future - keeping the load within the

boundaries of the increased capacity.

In

the depths of our own stress we all know colleagues we admired who never seemed

ruffled by increased workload, or by sudden life changes, and who seemed to have

infinite capacity.

Weight-on-a-Spring

model

Against

the background of imprecise definition of stress, the concepts of 'stressors'

and 'strains' were discriminated and offered to the students in a cause-effect

model. A 'stressor' might be work

overload, causing the 'strain' of fatigue. This is illustrated by the

Weight-on-a-Spring

model, the Weight representing the stressor and the extension the strain

(Russell 1953).

This

model was useful when first presented, but the students soon noticed that a

strain could switch to being a stressor, leading to a chaining effect. For

example, the strain of fatigue could become the stressor causing the strain of a

weakening family relationship. A

stress counselor should enter the chain by defining the stressor and strain at

point of entry. There is cost to a client, and difficulties for a counselor, who

fails to find the break-point of entry to a closed loop stressor-strain cycle.

Three-Systems

model

The

students were given local, national and global suicide and mortality figures,

with their relationships to variables such as socioeconomic

background and marital status.

This led to listings of stress-related illnesses.

The students showed wide variation in their beliefs about discrimination

and generalization of this concept, which was not surprising given the

background of an imprecise definition of ‘stress’ itself.

The students understood and accepted the Three-Systems Model of behavioral,

emotional and physical

interaction as described by Powell and Enright (1990), but they barely mentioned

it in discussion, counseling or essays. Perhaps

the students felt the model to be too naïve, obvious or inappropriate, even in

conditions where its originators saw its relevance.

Perhaps being a textual model it was easily forgotten.

However when students failed to observe behavioral, emotional and

physical changes at an early stage in a counseling situation, there were

cumulative difficulties in reducing client anxiety.

Type

A and B Personalities model

The

students realized that their problems could not only be blamed on the

environment but on their own reactions and interactions with it. The Type A and

B model of behavior traits (Friedman and Rosenan 1959; Glass 1977; Matthews

1982) was introduced. Its categorization was clear, but although the methods for

ameliorating excessive bias towards either trait were highly successful with a

few students, the model failed with the rest. A new model was proposed for

targeting a desirable but hypothetical middle-road Type ‘C’ behavior and

developed by role-play to even more satisfying Types D, E, F - - - and

subsequent behaviors, where for example reaction to a novel, unexpected event,

shock or emergency situation could be controlled to prevent disablement of

thought or action. Assuming

attitudes are difficult to change quickly by conventional methods (except by

unfortunate negative shock events), the students found that much practice was

needed to reach the ‘higher’ levels of C, D, E - - - behavior, beyond the

traditional Types A and B. For

example, at first, great control is needed to speak slowly when every set

instinct tells you to use quick and aggressive response.

Teachers are well trained in this technique when faced with challenging

students. Ways of affecting more rapid change would need to control or cope with

instinctive reactions. Students trained in using suggestion in hypnosis achieved

the most rapid results in changing destructive attitudes.

Life-Change

Units (LCU’s)

Shock

events like bereavement can effect rapid temporary or permanent change.

Illness or accident can trigger a person to initiate a worthy cause to

help similar victims. The students

completed the Holmes and Rahe (1967) Life-Change Inventory, but found that their

reactions to a life-change event were dependent on their hardiness, mental

stamina and parental or vocational training -

Life-Change

Model

This

model suggests that life changes or job changes cause the stress.

Life changes have been placed in a hierarchy.

At the top of the list is 'death of a spouse'.

'Christmas' and 'holidays' appear in the list as causing some people

stress, even though they are supposed to provide relaxation. Each life-change

item in the list is allocated a score. You

add your scores and the total indicates your stress level.

Perhaps

each profession should develop its own LCU’s. For example, teachers are

subject to their own list of internal life changes - sudden changes in

collaborative teams, the curriculum or family problems. Compilation of a

complete scored list focused on teaching would be a fruitful piece of research.

Test

Your Stress Level -

Read

through this list of life events and write down the Life Change Units (LCUs)

value for each that has occurred in the last 12-18 months.

Total

your Life Change Units (LCUs). If your score is 150 LCUs or less, your level of

stress based on life changes is low. If your score is 150-300 LCUs, your stress

levels are borderline - you should minimize changes in your life if possible at

this time. If your score is more than 300 LCUs your stress levels are high. You

should minimize other changes in your life if possible and work at instituting

some stress intervention techniques.

|

Ranking

of Life event |

LCU |

|

1.

Death of Spouse |

100 |

|

2.

Divorce |

73 |

|

3.

Marital Separation |

65 |

|

4.

Jail Term |

63 |

|

5.

Death of close family member |

63 |

|

6.

Personal injury or illness |

53 |

|

7.

Marriage |

50 |

|

8.

Fired from job |

47 |

|

9.

Marital reconciliation |

45 |

|

10.

Retirement |

45 |

|

11.

Change in health of family member |

44 |

|

12.

Pregnancy |

40 |

|

13.

Sex Difficulties |

39 |

|

14.

Gain of new family member |

39 |

|

15.

Business readjustment |

39 |

|

16.

Change in financial state |

38 |

|

17.

Death of close friend |

37 |

|

18.

Change to different line of work |

36 |

|

19.

Change in number of arguments with spouse |

35 |

|

20.

Mortgage/loan for major purchases |

33 |

|

21.

Foreclosure of mortgage or loan |

31 |

|

22.

Change in responsibilities at work |

29 |

|

23.

Son or daughter leaving home |

29 |

|

24.

Trouble with in-laws |

29 |

|

25.

Outstanding personal achievement |

28 |

|

26.

Spouse begins or stops work |

26 |

|

27.

Begin or end school |

25 |

|

28.

Change in living conditions |

24 |

|

29.

Revision of personal habits |

23 |

|

30.

Trouble with boss |

20 |

|

31.

Change in work hours or conditions |

20 |

|

32.

Change in residence |

20 |

|

33.

Change in schools |

19 |

|

34.

Change in recreation |

19 |

|

35.

Change in church activates |

18 |

|

36.

Change in social activities |

17 |

|

37.

Mortgage, or loan for lesser purchase (car etc.) |

16 |

|

38.

Change in sleeping habits |

15 |

|

39.

Change in number of family get-togethers |

15 |

|

40.

Change in eating habits |

15 |

|

41.

Vacation |

13 |

|

42.

Christmas |

12 |

|

43.

Minor violation of the law |

11 |

Stress

is the body's non-specific response to any demand placed upon it. It is

not caused only by negative or adverse influences. Stress increases the rate of

wear and tear the body experiences. Americans spend over nine billion dollars a

year to deal with stress.

Ritualistic

model

The

ritualistic model is related to the load capacity model and to the life change

model. It is based on a feeling that

things are out of control unless rituals are observed. Eventually this blocks

creativity and innovation. The rituals are not confined to working hours. They

start in the morning before work, where events ‘have’ to take place in a

habitual order, or stress is experienced. In the stress management course,

students were weaned from rituals by setting them a homework assignment to break

at first just one ritual. They said it was the most difficult assignment of the

course. Teachers know that a slight change in routine can upset the discipline

of a class. It might be a snowfall starting or a bird settling outside the

classroom window. Perhaps the education system should devote itself in the

affective domain to teaching children to react appropriately to novel

situations, essential for encouraging creativity.

Moving

animal model

A

simple ‘moving animal’ model was found to be very effective. A tiger was

drawn on one overhead projector slide and jungle camouflage on another. The two

slides were placed on top of each other on an overhead projector.

The animal is only noticed when the overlapping slides are moved relative

to each other. The analogy in stress management is that many people are happy to

preserve the status quo and only experience stress when changes are made in

their working life. This model

helped to exercise the ‘detector function’ described later in Kuhn’s model

(1974).

Microstressors

model

To

complement the life change inventory, the effects of cumulative small stressors

were examined. Research articles have started to appear showing for example some

evidence of a link between these 'microstressors' and depression (

Assertiveness-Relaxation

model

Many

of the students asked to be taught Assertiveness. In its mid-ground between

passivity and aggression, or between reactive and proactive response,

Assertiveness asks for students to move between these attitudes.

Like switching between Type A and B, it was difficult to break lifelong

habitual responses to situations. Relaxation techniques were the ameliorating

catalyst to change, but some students still found it paradoxical to combine

assertiveness with relaxation. Relaxation was therefore practised both in

preparation for being more assertive when rights were infringed and also for

defusing the aggression of other people. For most students extensive role-play

and feedback from external situations effected the desirable responses.

Learning curves model

When

students realized that stress management would often involve simultaneous

changes to themselves and to their environment a return to the first principles

of learning was needed. They had to learn how to learn new responses to

stressors. This was difficult because of their ritualizations. Cleeton (1991)

profiled learning barriers, not only in the cognitive domain, but also in the

functional and experiential domains. Functional learning barriers to stress

management may be lack of confidence, lack of assertiveness, family problems or

conflict between work and home. Experiential learning barriers may be lack of

experience in dealing with problems normally arising at work or home. The

students were shown examples of learning curves -

Curve

showing a linear rate of learning

achievement

steep

(fast learner)

|

shallow

(slow learner)

![]() time

time

Curve

showing linear learning, but starting from some previous knowledge

achievement

|

--------Previous knowledge

![]() time

time

More

realistically, the following curve shows how many of us learn. It is called the

‘stepped-change model’. For example, when we learn how to play a musical

instrument, we achieve an elementary level quite rapidly, and then seem to

‘stick’ at that level and think we will never rise above it. After a number

of steps, we may reach a ‘plateau’ where we either give up the practice and

learning, or realize that we have reached the limit of our persistence or

ability

-

Curve

showing stepped learning

achievement

![]()

plateau

plateau

step

time

The

following curve reproduces an actual performance by an adult learner. At first

the learning was ‘ideal’, accelerating as knowledge accumulated along an

exponential curve – a ‘knowledge explosion’. Then the learner discovered a

barrier and fell into a discouraging ‘ditch’ of learning. Recovering, but

lacking confidence, the learner could not achieve accelerated learning, but only

linear learning. A second fall into a ditch leaves the learner so discouraged

that some previous learning could not remembered (a learning ‘block’), but

eventually recovery took place to reach a plateau of ability and persistence.

Learning

Curve showing actual performance of an adult learner

achievement

![]()

plateau

linear

learning -

ditch

ditch

accelerated (‘ideal’) learning

![]()

time

The

following curve shows ‘ideal’ learning, usually produced by material which

is challenging but not anxiety-producing. It shows ‘accelerated learning’

– an exponential rise in achievement with time, knowledge cumulatively

capitalizing on previous knowledge, setting off a knowledge explosion.

‘Ideal’

Learning Curve

achievement

![]()

time

Relating

these curves to stress management, students need to strive for ‘ideal’

exponential learning and avoid ‘ditches’ and ‘plateau’. Stress

management involves lifelong learning because novel stressors are always

presenting themselves with changes to the individual, the environment and with

local, national and global change.

Perception

and Reality model

Learning

Barriers

The

author (Cleeton G., 1996) developed terminology to describe learning barriers.

Have you ever heard adults or children say, ‘I can’t do Math’? They are

expressing a perceived learning

barrier. In practice the barrier may be real

or illusory. Sometimes a child will

say they can’t do Math, but be able to manipulate and tell you the statistics

of all their team’s baseball games. In that case the barrier must be to some

extent illusory. When adults return to

the classroom after a gap of many years, they are often scarred with memories of

failure in school, sometimes from bad teaching, for example from teaching

abstract before concrete operations. These scars caused ditches in their

learning curves. Gentle teaching to remove the scars and getting them to realize

that it was not their fault can relegate their perceived barriers into illusory

barriers.

Sometimes

perceived barriers will be expressed

in more serious terms or at specific levels. A child might say, ‘I can’t do

Math, and what’s more I never will be able to do it’. This suggests that

there is a hierarchy of learning

barriers. An older learner might

say, ‘I can’t do complex numbers, and what’s more I never will be able

to’.

Before a

course starts, a potential student may scan the syllabus and express anticipated

learning barriers for the whole or part of it, for example -

‘I anticipate difficulties with genetics’. This can cause a damaging

mindset. Piaget and Inhelder (1971) said, ‘That which is anticipated is more

likely to occur’ - an example of ‘negative’ or pejorative visualisation.

In

stress management the tutor needs to demonstrate that many anticipated and perceived

barriers can be illusory, and also

teach how to overcome real barriers.

In preparing lessons we tend to concentrate on motivation to make lessons

interesting, but we should also forecast, acknowledge and aim to surmount

learning barriers. Learning barriers will be encountered in the Substantive

(subject matter) domain, for example caused by faulty sequencing of the

material. They can also be in the Functional

domain, for example caused by disability or family problems. They can be in the Experiential

domain, for example caused by lack of practical experience in needed skills.

There are several models of learning barriers. Early models by Lewin (1935)

showed barriers as obstructing goals,

in an environment which was to a greater or less degree permeable. As teachers

our role is to set the goal and make the teaching environment as permeable and

flexible as possible to surmount the learning barriers.

An

insidious learning barrier is the discovered

barrier. This is neither anticipated before the course starts, nor perceived by

the student when the course starts, but is unexpectedly discovered by student and teacher as the course proceeds. Not even

the best pre-course syllabus can forewarn potential students about discovered

barriers. Such barriers can approach the learner at high or low speeds, can have

fast or slow attacks and fast or slow decays. Their profiles will resemble those

generated by music synthesizers –

Learning

barrier with fast attack and slow decay

barrier

height

Learning

barrier with slow attack and fast decay

barrier

height

|

Learners

are not particularly realistic about their learning potential. The author (Cleeton,

G., 1996) found that they were notorious in their discrepancies between

perception and reality. Mostly they were pessimistic, sometimes optimistic.

Skilled teaching can bring them into reality without discouragement.

Weaknesses

were apparent in students' decision-making skills. They tended to act either in

a stereotyped way when faced with novel outbreaks of stress, or at the other

extreme would vacillate between trial of different solutions. They also

experienced dissonance - avoiding alternatives when a decision had been made and

brooding with regret, so salience of their dissonance was not resolved (Festinger

1993). Models of learning

strategies, decision-making and risk-taking were studied in the context of

innovation theory. The Reality-Perception of Reality model became accepted and

was used with success in reducing the discrepancy index (Fisher 1986) between

perception and reality.

Child-Within

model

Students

also noted discrepancy between perception and reality in conflicts between the

conscious and subconscious minds. A client might say, consciously

and conventionally, ‘I love my sister’, but subconsciously, in

regression, say, ‘I hate my sister’. Instances of emergence of the ‘child

within’ were sensitized by regression. Problems were reported of ‘childish

adults’ and indeed ‘adult children’. Reluctantly some of these effects

began to be recognized by the students as lying within themselves and led to

their determination to remove the ‘bugs’ from their systems before

practising stress management on other people.

Time

management model

The

stressors of learning and of meeting targets were approached through time

management and just-in-time management, keeping long-term diaries of activities,

relaxation and thinking. Reorientation

of waking and sleeping patterns were accepted by some students but strongly

resisted by others. The

possibilities of instant sleeping and waking by suggestion in hypnosis were

explored, in conjunction with subliminal learning.

Marionette

on Strings model

The

human being is a delicate instrument, partly controlled by ‘strings’ to the

different people in his/her life. When

one of these people pulls a string that attached to the human being too tightly,

the string or the human being can ‘snap’ and be either mentally, physically

or both mentally and physically destroyed. Other

people pulling the strings might be able to compensate for this loss, but in

some cases the person may have to completely break ties with the stressor.

For example, if the stressor is an employer, the person might have to

resign to save mental and physical health.

Shifting

the Goal Posts model

The

person is told to complete a task. When

near completion, the controlling person changes the path and targets of the

task. This causes intense stress because everything done up to this point has to

be altered to suit the new instructions.

Mountain

out of a Molehill model

You

have to teach simple material that should only take a few minutes to explain,

but fill one hour in time to do it. This is a stressor for teachers, professors,

or anyone lecturing. Sometimes you

are given a topic to talk about which in common sense terms can be stated in a

few minutes to almost any audience. You have to stretch this to an hour. You

have to inject stories, personal experiences, etc., but as you listen to

yourself (if you could) you are restating the original premise over and over

until you are completely burnt out. This

can make you mentally and physically ill and does not serve as a benefit to your

audience either. It is making something more important than it is.

Contagion

of stress model

Most

of us have experience of the ‘weak link in the chain’ when working as a

team, for example the person who holds up the work by not meeting deadlines.

When prolonged this behavior can be contagious.

Contagion

of stress called for a model based on the two-way spillover of strain between

occupation and home (Cooper and Marshall 1976, French and Caplan 1972).

This necessitated assembly and modeling of family relationship stressors

and occupational stressors, and the interaction between them.

Power,

Role, Task and Person model

Occupational

stress was modeled through analysis of the Power,

Role, Task and Person structures of organizations (

Their

structural strengths and weaknesses were assessed in terms of (i) their

stability, (ii) their resistance to change, development or recessional crises

and (iii) how individuals of different personality might fare in them, or be

matched to a structure by choice.

The

following descriptions of the structures are due to

The

power culture is most often found in small entrepreneurial organizations.

Its structure can be pictured as a web.

The

power culture depends on a central power source with rays of power and influence

spreading out from that central figure. The rays may be connected by functional

or specialist strings but the power rings are the centers of power and

influences.

This

organization works on precedent and by anticipating the wishes and decisions of

the central power sources. There are few rules and procedures and little

bureaucracy. Control is exercised from the center. It is a political

organization in that decisions are taken largely based on the balance of

influence rather than on logical or procedural grounds.

A

power culture can move very quickly and react rapidly to threats or

opportunities. These cultures put a lot of faith in the individual, little in

committees. They judge by results and care very little about the means used to

obtain results. Size is a problem for power cultures; when they get large or

when they seek to take on too many activities, they can collapse.

________________________

The

role culture is called a bureaucracy. The structure for a role culture

can be pictured as a Greek temple.

The

role culture works by logic and rationality. Its strength in its its pillars or

functional specialties, e.g. the finance department, the technical services

department, the public services department. The work of the functional

departments is contro lled by:

| Procedures for roles -- Job descriptions,

authority definitions | |

| Procedures for communications -- required sets

of copies of memos | |

| Rules for settlement of disputes -- appeal

process. |

The

functional departments are controlled at the top by a small group of senior

managers (the pediment of the temple). It is assumed that these folks are the

only co-ordinators required if the separate departments do their job as laid

down by the rules and procedures and the overall plan.

In

the role culture, the job description is often more important than the

individual who fills it. Individuals are selected for satisfactory performance

of a role and the role is usually so described that a range of individuals can

fill it. Performance above and beyond the role prescription is not required and

can even be regarded as disruptive. Position power is the major power source;

personal power is frowned upon and expert power limited to its proper place. The

efficiency of this culture depends o n the rationality of the allocation of work

and responsibility rather than on individuals.

The

role organization will succeed very well in stable environments where little

changes from year to year and predictions can be made far in advance. Where the

organization can control its environment, where its markets are stable,

predictable or controllable, the rules and procedures and the programmed

approach to work will be successful.

Role

cultures are slow to perceive the need for change and slow to change even when

the need is seen. If the market, the product/service needs, or the environment

changes, the role culture is likely to continue without change until it

collapses or until the top management is replaced.

Role

cultures offer security and predictability to the individual -- a steady rate of

ascent up the career ladder. They offer the chance to acquire specialist

expertise without risk. They tend to reward those wanted to do their job to a

standard. A role culture is frustrating for the individual who is power-oriented

or who wants control over his/her work. Those who are ambitious or more

interested in results than method may be discontented, except in top management.

The

role culture is found where economies of scale are more important than

flexibility and where technical expertise and depth of specialization are more

important than product innovation or product cost.

__________________

The

task culture is job or product oriented or focused on service delivery.

Its accompanying structure can be represented as a net.

Notice

some of the strands of the net are thicker and stronger than the others. The

power and influence in a task culture lies at the intersections. A matrix

organization is one form of the task culture.

The

task culture seeks to bring together the appropriate resources, the right people

at the right level of the organization, and then to let them get on with it.

Influence is based more on expert power than on position or personal power,

although these power sources have an effect. Influence is more widely dispersed

than in other cultures and each individual in the culture tends to think he/she

has influence.

The

task culture is a team culture where the outcome, the result, the product of the

team's work tends to be the common goal overcoming individual objectives and

most status and style differences. The task culture uses the unifying power of

the group to improve efficiency and to identify the individual with the

objective of the organization.

The

task culture is highly adaptable. Groups, project teams, or task forces are

formed for a specific purpose and can be reformed, abandoned or continued. The

net organization works quickly since each group ideally contains within it all

the decision-making powers required. Individuals have a high degree of control

over their work in this culture. Judgment is by results. There are generally

easy working relationships within the group with mutual respect based upon

capacity rather than age or status.

The

task culture is appropriate where flexibility and sensitivity to the market or

environment are important. The task culture fits where the market is

competitive, where the product life is short, where speed of reaction is

important.

The

task culture finds it hard to produce economies of scale or great depth of

expertise. Large scale systems are difficult to organize as flexible groups. The

technical expert in a task culture will find him/herself working on various

problems and in various groups and thus will be less specialized than his/her

counterpart working in a role cultures.

Control

in a task culture is difficult. Control is retained by top management through

the allocation of projects, people and resources. But little day-to-day control

can be exerted over the methods of working or the procedures without violating

the norms of the culture. Task cultures flourish when the climate is agreeable,

when the product is all-important, when the customer is always right, and when

resources are available for all who can justify using them. ( ‘for example

putting a Man on the Moon by 1970’ – Ed.)

When

resources of money and people have to be rationed, top management may wish to

control methods as well as results. When this happens, team leaders begin to

compete for resources using political influence. Morale will decline and the job

becomes less satisfying as individuals begin to reveal their individual

objectives. When this happens the task culture tends to change to a role or

power culture.

The

task culture is usually the one preferred as a personal choice to work in by

most managers especially those at junior and middle levels. It is the culture

which most of the behavioral theories of organizations point towards with their

emphasis on groups, expert power, rewards for results, merging individual and

group objectives. It is the culture most in tune with current ideologies of

change and adaptation, individual freedom and low status differentials.

________________________

The

person culture is an unusual one and won't be found in many organizations

but many individuals cling to some of its values. In this culture the individual

is the central point. If there is a structure or an organization it exists only

to serve and assist the individuals within it. If a group of individuals decide

that it is in their own interests to band together in order to do their own

thing more successfully and that an office, a space, some equipment, some

clerical support would help, then the resulting organization will have a person

culture. Architectural partnerships, real estate firms, some research

organizations, perhaps information brokers often have this person orientation.

Its structure is minimal, a cluster or galaxy of individual stars may be the

best picture.

As

most organizations tend to have goals and objectives over and above the set of

collective objectives of their members, there are few organizations with person

cultures. Control mechanisms or even management hierarchies are impossible in

their cultures except by mutual consent. The organization is subordinate to the

individual and depends on the individual for its existence. The individual can

leave the organization but the organization seldom has the power to evict an

individual. Influence is shared and the power base is usually expert.

The

kibbutz, the commune, the co-operative, are strivers for the personal culture in

organizational form. Rarely does it succeed beyond the original creators. Very

quickly the organization achieves its own identify and begins to impose it on

its individuals. It becomes a task culture at best, but often a power or role

culture.

Although

there are few organizations with person cultures, many individuals with a

personal preference for this type of culture operate in other kinds of

organization. Specialists in organization often feel little allegiance to the

organization but regard it rather as a place to do their thing with some benefit

accruing to their employer. Individuals with this orientation are not easy to

manage. As specialists employment elsewhere is often easy to obtain so resource

power has less potency. They rarely acknowledge other people's expert power.

Coercive power is not usually available which leaves only personal power and

such individuals are not easily impressed by personality.

___________

Within

an large organization different types of cultures may be found as shown in the

diagram below:

The

second diagram (due to Harrison 1972) below points out some of the organization

design policies variables that need to be considered when considering the nature

of an organization and its fit with its environment.

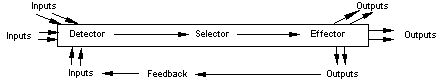

Detector,

Selector, Effector model

Students

had by now realized that that success in stress management would not only

involve changes in the environment but also changes in themselves, with feedback

between these two systems.

The

most sophisticated model introduced to the students was that due to Kuhn (1974).

It proposes the organism has Detector,

Selector and Defector functions,

is set within its environment and has feedback between these three functions

through the environment -

A closed system is one where

interactions occur only among the system components and not with the

environment. An open system is one that receives input from the

environment and/or releases output to the environment. The basic characteristics

of an open system is the dynamic interaction of its components, while the basis

of a cybernetic model is the feedback cycle. Open systems can tend toward higher

levels of organization (negative entropy), while closed systems can only

maintain or decrease in organization.

Kuhn

suggested that strain arises from neglect, damage or insensitivity in one or

more of the three functions - Detector,

Selector and Effector - so the

students practised exercises of each function.

Some students preferred textual rather than image presentation of the

model. Having applied the Kuhn

model, some students were able to inject a fine structure proposed by Kuhn,

where each of the three functions has its own Detector, Selector and Defector.

Although comprehensive, students felt that the model was only a step

towards presentation of a simple ‘magic-key’ model, similar to the ‘moving

animal’ model, which would be applicable to most situations and spin off a

universal definition of stress.

|

|

Overview of the stress models

|

Model |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Tap

and Jug |

Simple |

Inadequate,

makes false assumptions |

|

Capacity

- Demand |

Simple |

Inadequate,

too specific |

|

Weight

on a spring |

Defines

stressors and strains |

Chaining

of stressors and strains |

|

Three

systems |

Observation

of early warning signs |

Difficult to remember, too textual for Imagers |

|

Type

A and B |

Coping

strategy |

Difficult

to practise necessary changes. Inconsistent

- ignores microstressors. |

|

Life

change units |

Clear

categorization |

Insufficient

detail for specific occupations |

|

Ritualistic |

Benefits

of gaining flexibility |

Difficult

to break rituals in a short time |

|

Moving

animal |

Vivid presentation -immediately useful, also later

in complex |

Too

specific |

|

Microstressors |

Useful

relationships emerging for depression |

Tedious

to record Microstressors and their subsequent strains |

|

Assertiveness-relaxation |

Popular

need |

Paradoxical |

|

Learning

curves |

Confidence-building,

overcomes fear of innovation |

Student

preference to retain destructive status-quo |

|

Perception

and reality |

Challenges

cherished assumptions |

Too

textual for Imagers |

|

Child

Within |

Recognizes

suppressed events |

Unpopular

for those who must see causal strain-stressor connection |

|

Time

management |

Connects

time management with personality |

Needs

long-term record-keeping |

|

Marionette

on Strings |

Involves

personal relationships |

Tends

to absolve individual from change |

|

Shifting

the Goal Posts |

Useful

for meeting deadlines |

Assumes

powerlessness |

|

Mountain

out of a Molehill |

Prioritizes

tasks |

Assumes

powerlessness |

|

Contagion |

Issues

warning signs of stress accumulation |

Difficult

to disentangle connections |

|

Power,

Role, Task and Person |

Understanding

structure in which one works |

Ignores

personality clashes within structures |

|

Detector,

Selector, Effector |

Comprehensive,

open to expansion |

Complex,

suggesting need for simplification |

Discussion

Many

stress management courses have had to follow the pattern of counseling based

upon vague definitions of stress, which leads to loss of focus. In this course a

list of stressors was assembled and existing stress models progressively

presented to fit new situations of strain. Diverse

models had to be remembered and fitted to diverse problems. Students leaving the

course felt that the necessary transfer to novel outbreaks of stress had not

been achieved. Where there was

contagion of stress, for example from workplace to home and back to workplace,

students often failed to enter or break the vicious circle.

As

seen by present students the Perception-Reality and Child-Within models offer

greatest promise. They cope with variations in life goals. In amelioration of

strains they open a way to philosophical and metaphysical discussion of life

purpose. They are complementary to regression for examination of suppressed

childhood experiences. They bridge traditional and alternative healing.

In

the fundamental problem of finding the cause rather than treating the problem,

frequently the default has to be that of giving coping strategies for the strain

when inability or incompetence has failed to reveal the stressor.

Many

students felt that previous counseling proposed too close a binding between

cause and effect, for example – ‘Your fear of water is because you lived

near a canal when you were a

child’. It may be prudent to

consider the possibility that sometimes there may be no such binding - that

there is an element of chance whether an unfortunate child event causes adult

anxiety, depression or phobia. If the focal causal event is exposed, for example

in hypnotic regression, the strain may be eliminated without there being obvious

cause-effect connection. Similarly in the human variation of response to events,

there may be no relationship between the severity of a problem and the severity

of the cause (and therefore severity or duration of treatment).

Proposals

for new modeling of stress

In

the absence of explicit definition of stress, new models will constantly been

needed. This situation is paralleled by other systems in their infancy of

stubborn resistance to definition. It may be profitable to step outside the

situation to look at a different philosophical or material database. When

searching for the text string ‘model plus generation’ in Social Science

databases, only a few matches were recorded.

In

contrast, Pure Science databases yielded numerous responses, revealing

familiarity with analogous situations, where complex models could mirror

mixtures of thin slices of quantitative data with large slices of qualitative

information. For example, the ‘state space framework’ was used by Patterson

(1995) to apply a model integrating data generation process with data

measurement.

Methodologies

of kinetic modeling and mechanistic studies of complex catalytic chemical

reactions have been analyzed by Gabrielle, Denoroy and Reau (1995). They showed

the rationality of a methodology based on advancement and discrimination of

hypotheses and gave a review of techniques for hypothesis generation. A

combinatorial algorithm and a library of chemical reactions were used.

Potthof, Holahan and Joiner (1995) examined a mechanism through which

interpersonal vulnerability factors may be linked with depressive symptoms by

integrating the stress-generation model with an interpersonal theory of

depression. Initial depressive

symptoms and initial reassurance-seeking style were positively associated with

the occurrence of microstressors. The results support our students’ perceived

usefulness of the model of accumulation of microstressors. Landis (1994)

launched a new series of metropolitan simulation models which replicated urban

growth patterns and impacts of development policy.

The rationality of the model and the way it has been built in terms of

its formal structure, its databases and its decision rules is explained.

Our

students often failed to disentangle the multiplicity of perceived strains which

they experienced and some of them could not weight the importance of multiple

macro-strains and microstressors leading to their present anxiety states. This

indicates the potential for multifactorial modeling, such as used by Rosenheck

and

Since

the strains defined by student-counselors in their clients may be wrongly

attributed to stressors, the top-down approach to modeling may be the way

forward. The techniques of reverse

engineering might be adopted. Puntambekar,

Jablowlov and Sommer (1994) presented a review of the techniques available for

reverse engineering, with particular emphasis on three-dimensional model

generation. It could be a promising

way to introduce programming of the computer to strain-stress simulation and

modeling. Reverse engineering is a

methodology for constructing computer-aided design models of physical parts, in

circumstances where the drawings of those parts are not available by the normal

methods of (i) digitizing an existing prototype, (ii) creating a computer model

and (iii) using it to manufacture the component. An analogy can be seen with

strain-stressor relationships in absence

of precise definition of stress. The criteria for a good model of stress would

be simplicity, adequacy to facilitate counseling in known categories and

flexibility to cope with new strains. At

the base level, models are icons for images to hold a problem in view and

remember the connections.

Glenberg

and Langston (1992) investigated the building of mental models by using pictures

in text, suggesting that a picture might provide relatively easy maintenance of

some other representational elements corresponding to parts in the picture,

freeing up capacity for inference generation. Perhaps stress models should

perform a similar function as a ‘holding and stacking area’, ready for

landing the stress management and coping skills when the problem has been

analyzed. The proliferation of models by brainstorming may be the only path to a

definition of stress. However Kometsky and Markowitz (1978) drew attention to

the danger of superficial resemblances when evaluating the problem of goodness

of fit of a model. Holyoak and Thagard (1995) have acknowledged the usefulness

of analogy in generating creative insights, but drew attention to examples of

dangerous errors which can arise.

Mental

models have been studied by Rhees (1983), Craik (1973) and Johnson-Laird (1991),

who maintained that the mind constructs ‘small-scale models of reality that it

uses to anticipate events, to reason and to underlie explanation.

The models are constructed in working memory (the mind actively

interpreting newly presented information and integrating previously stored

information) as a result of perception, the comprehension of discourse or

imagination. Their structure represents something about the world and can best

be described in terms of ‘problem solving’. In problem solving the task of

constructing a mental model involves making assumptions about the problem and

understanding the meaning of terms in the problem in order to reach a conclusion

(solve the problem). However, an

alternative model which is consistent with the statement of the problem might be

possible. The Theory of Mental

Models (Johnson, Laird and Byrne, 1991) predicts that a problem is more

difficult to solve if more than one model has to be considered.

Additional models impose a load on limited working memory.

External

representations (colloquially the ‘rough work’ we do to make models or solve

problems) are in the world as physical symbols (e.g. written symbols, beads of

abacuses, etc) or as external rules, constraints or relations embedded in

physical configurations (e.g. spatial relations of written digits, visual and

spatial layouts of diagrams, physical constraints in abacuses, etc.).

Internal representations are in the mind as propositions, production

schemas, mental images and other forms. According to Travers (1993) when one

begins a problem-solving task one mentally visualizes and arranges the givens,

so all representation commences as internal. Cox and Brna (1995) maintained that

concerning the nature of internal representations, popularly debated within

cognitive science, advocates can be found for the position that internal imagery

is merely epiphenomenal (concomitant to it).

External

representations (Ers) are short lived or idiosyncratic. Studies in literacy show

the important functions of Ers. The

classical view on writing, originally developed by Aristotle and presently

restated by

Pemberton

and Sharples (1996) supported the view that Ers are the markings that writers

make, singly, or in collaboration, on some external medium such as a computer

screen. They include notes, topic

lists, written plans, idea maps, outlines, or tables, concept maps, argument

structures and annotations on the draft document in all its stages.

An example of an Er is a simple ad-hoc sketch (or even a shape described

in the air or via a trace with a finger on a desktop) indicating intentions that

are too amorphous to express easily in words.

Wood (1992), in his studies of pairs of collaborating authors, pointed

the authors to draw a large funnel shape to represent the overall structure of

the paper, and later both authors cited different places in this shape when

talking about the same parts of the paper. Pemberton and Sharples suggested the

Ers could in some instances be too ambiguous and could be resolved by writing

down a more precise form of words.

When

a sample of people is asked to describe their stress by placing it within a

stress model, they give different answers to what the stress model meant to them

as an individual.

Student-tutor

experiences with stress modeling suggests the need for re-examination of the

thinking processes by which subject-independent models are generated both inside

and outside this specific field. Promising directions seem to be those of

reverse engineering and computer-simulation of strain-stressor relationships,

and teaching enhanced skills in external representation. These will be the

immediate directions of future research in constructing stress models.

References

Cleeton

G.(1991). Development and

application of a new theory of learning barriers.

Ph.D. thesis, University of Keele.

Cleeton G. (1996). Perception and Reality of Learning

Barriers. Perceptual and Motor Skills,

1996, 82, 339 – 348.

Cooper

C.L. and Marshall J. (1976) Occupational sources of stress a review of

the

literature relating to coronary heart disease and mental ill health. Journal

of

Occupational Psychology, 49,

11-28

Cox,

R. and Brna P. (1995) Supporting the use of external representations in problem

solving;

The

Journal of Artificial Intelligence In Education, 6(2/3), 239-302.

Craik

F. (1973) “Levels of Analysis” view of memory.

IN P.PLINER et al. (Eds.),

Communicattion

and affect: language and thought.

Eysenck,

M. H. (1989). Personality, Stress

Arousal and Cognitive Processes in Stress transactions.

In Neufeld R W J (Ed) Advances in

the Investigation of

Psychological

Stress, 133-157.

Everly

G. S. and Rosenfeld R. (1981). The

Nature and Treatment of the Stress Response, Plenum,

Festinger

L. (1993). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.

French

J.P.R. and Caplan R D (1972). Organizational

Stress and Individual Strain. In

Marrow A J (Ed), ‘The Failure of Success’.

Friedman

M. and Rosenman R.H. (1959). Association

of specific overt behavior pattern with increases in blood cholesterol,

blood-clotting time, incidence of arcus senilis and clinical coronary artery

disease. Journal of the

American Medical Association 169,1286 -- 1296

Gabrielle

B, Denoroy, P. and Reau R. (1985)

Nitrogen dynamics in a colza planatation-modelling ecological impact.

OCL-Oleagineux Corps Gras Lipides, 2. 1,8-10.

Glenberg

A.M. and Langston W.E. (1992). Comprehension of illustrated text:

Pictures help to build mental models. Journal of

Memory and Language, 31, 2,129 -- 150

Holyoak

K. J. and Thagard P. (1995). Mental

leaps: Analogy in Creative Thought.

Holmes

T.H. and Rahe R. H. (1967). The

social readjustment rating scale. Journal

l of Psychosomatic Research, 11,213 --218.

Johnson-Laird

P. and Byrne R. (1991) Deduction.

Kometsky

C. and Markowitz R. 1978.

Animal models of schizophrenia. In

Lipton M.A., DiMascio A., Killiam K.F. (eds). Abio-informational theory of

emotional imagery. Psychophysiology,

16:495-2512.

Kuhn

A. (1974) The Logic of Social Systems. San

Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Landis

J. D. 1994. The California Urban

Futures Model - Anew generation of metropolitan simulation models.

Environments and planning, 21, 4,399 -- 420.

Lolas

F. (1979). The pertinence of animal

investigation for clinical stress research.

Neurobiologia., 42: 185 -- 192.

Matthews

(1982). Psychological perspectives

on the type - A behavior pattern. Psychological

Bulletin, 91,293-2333.

Patterson

(1995). An integrated model of the

data measurements and data generation processes within application to

consumers’ expenditure. Economic

Jouirnal, 105, full to wait, 54 -- 76

Pemberton

L. and Sharples R. (1996) External

Representations in the Writing Process and How to Support Them. AIEd 96 External

Representations.

Potthoff

J.G., Holahan C.J. and Joiner T.E. (1995) Reassurance

seeking, stress generation and depressive symptoms -- an integrative model.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68, 4,664 -- 670.

Puntambekar

N.V., Jablokow A.G. and Sommer, H.J. (1994) Unified review of 3D model

generation for reverse engineering. Computer

integrated Manufacturing Systems, 7, 4, 259-268.

Powell

T. J. and Enright S. (1990) . Anxiety

and Stress Management. Tavistock.

Rosenheck

R. and

Rhees

R. and Anscombe G. (1983) Ludwig Wittgenstein, Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics

Russell

R.W. (1953). Behavior under stress.

International Journal of

Psychoanalysis, 54, 1 -- 12.

Sassure

F. (1983) Courses in General Linguistics London: Duckworth.

Travers

J. (1993) Effectuve Teaching,

Effective Learning.

Wood

C. (1992). A cultural-cognitive

approach to collaborative writing. Cognitive

Science

Research

Paper CSRP 242,

Wycherley

(1997). The Living Skills Pack.

South

Yerkes

R.M. and Dodson J. D.(1908). The

relation to strength of stimulus to rapidity of how the formation.

Journal of Comparative and

Neurological Psychology. 18, 459

-- 482.

*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*~*